Understanding The Tech Layoffs. Could They Have Been Prevented?

Time to talk about layoffs, a topic nobody likes. And while you may consider layoffs a “case of bad management,” let me convince you otherwise. In some sense they’re just a fact of life, and often we simply need them. Here is my argument.

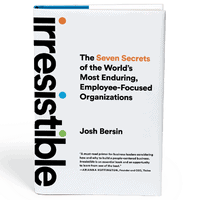

The Growth Cycle Of A Business

Companies, like people, go through cycles of growth. In the early stages, often fueled by investors, the company grows quickly. It’s easy to double or triple revenue the first few years, which creates demand for hiring. So fast-growth companies focus on hiring before all else, trying to attract the best engineers, the best marketing people, and best sales people as fast as they can.

As the company grows, things slow down. You’ve reached early adopters, you start to see competition, and sales people need training. You’re no longer the only game in town and you need to focus on product marketing, sales productivity, and a focused go-to-market strategy. Hopefully you’ve found the flywheel of your company (read Jim Collins), but the company has become more complex. Startup managers need to learn new skills, and you may need more seasoned leadership.

This happens to tech firms all the time. When I worked at Sybase years ago, and we had a competitive edge on Oracle so our business strategy was to “Get Big Fast.” This mantra, which is often used in Silicon Valley, means “hire as fast as possible.”

|

Many companies manage this well, by the way. ServiceNow, Workday, ADP, and many great HR Tech vendors understand this well. These companies invest heavily in marketing and product management, they focus on continuous sales training, and they build a “moat” of customers, employees, and recurring revenue that scales.

In tech and consumer businesses, growth is dependent on innovation. When a company lets down their guard (Netscape, AOL, even Facebook), things can slow down fast. (Witness the layoffs at Salesforce, Meta, Lyft, and others.)

At some point (Cisco has faced this), the growth cycle comes to an end. The core product hits a wall and it’s time to build a new growth vector. In the case of Salesforce, they’ve been on an acquisition spree and many analysts think they’ve lost their ability to innovate. Companies like Meta face existential decisions: do we make Instagram and Facebook more relevant or do we start all over?

Mature companies have been dealing with this for decades. IBM, Microsoft, and ADP have reinvented themselves many times. Defense contractors lose large contracts and lay off the entire team as a program concludes. And Consumer Packaged Goods companies continuously move people into new brands as consumer needs change. These companies have learned that “intelligent talent mobility” is often a better solution than letting a lot of people go.

As I discuss in my podcast, I went through this at IBM in 1989, at Sybase in the late 1990s, and at DigitalThink in the early 2000s. In each case the company I worked for was run by smart and forward thinking people but got caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. And in fast-moving markets like Tech, Social Media, Telecommunications, Airlines, and Entertainment, this happens faster than you think.

Do You Need A Layoff or Not?

And this begs the big question: when the business slows dramatically, do you really need a layoff? As I discuss in Beware Of The Layoffs, companies have decisions to make. If you’ve avoided the hiring frenzy and grew slowly and deliberately, you may just need a hiring freeze. If it gets worse you may need a pay cut or reduction in benefits. But then it comes down to great management.

Can your leadership team convince people to sacrifice on behalf of the company, take on new responsibilities, and move from the “slow growth” to “fast growth” areas of the business? Have you built the culture of learning, mobility, and teamwork to facilitate this internal reinvention? Will the team take a pay cut or cut in benefits to preserve their jobs?

If you read my book Irresistible, you are likely ready for this disruption. But if you’re like many fast-growing companies and you didn’t see this coming, you can’t move fast enough. The cash balance, investors, and stock market speak loudly, and you have to let people go.

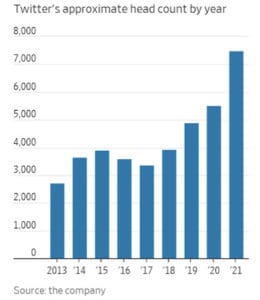

In some cases (ie. Twitter, Meta, RobinHood, Better.com, Stripe), the company mis-read their opportunity. You can blame management or you can blame investors who told the CEO “hire as fast as you can.” Some times it’s the stock market or investors that force the process. And then there are special cases: when Elon Musk agreed to pay $45 Billion for Twitter he more or less guaranteed that layoffs would be required.

In some cases (ie. Twitter, Meta, RobinHood, Better.com, Stripe), the company mis-read their opportunity. You can blame management or you can blame investors who told the CEO “hire as fast as you can.” Some times it’s the stock market or investors that force the process. And then there are special cases: when Elon Musk agreed to pay $45 Billion for Twitter he more or less guaranteed that layoffs would be required.

In other cases a layoff it simply marks the end of a business unit, the shutdown of an underperforming operation, or a reorganization to adjust to change. Oracle recently closed it’s largest ever acquisition, Cerner. This deal, which was Oracle’s largest ($28 Billion), brings enormous new growth. But to get there from here Oracle has to redeploy sales, marketing, engineering, and internal operations. So suddenly there are too many people.

Even Microsoft, one of the most admired tech companies in the world, laid off thousands in 2014 as it exited Nokia and other slow growth businesses.

How To Avoid This Situation

Layoffs have several negative effects: they can spook investors, the company loses valuable skills, and surviving employees feel uncertain. It often takes a year or two for a company to “recover” from a layoff, and some companies never return to pristine growth. But nevertheless, this is a common business situation, so let me give you some ways to avoid it.

First, you can be a conservative leader. Yes, the market is growing and you see unlimited opportunity. But have you and your management team really sat down and discussed the worst case scenario? Companies are not like stocks: you can’t just “divest” at a moment’s notice. Each step toward growth creates infrastructure to support – so great managers look ahead and plan for the worst.

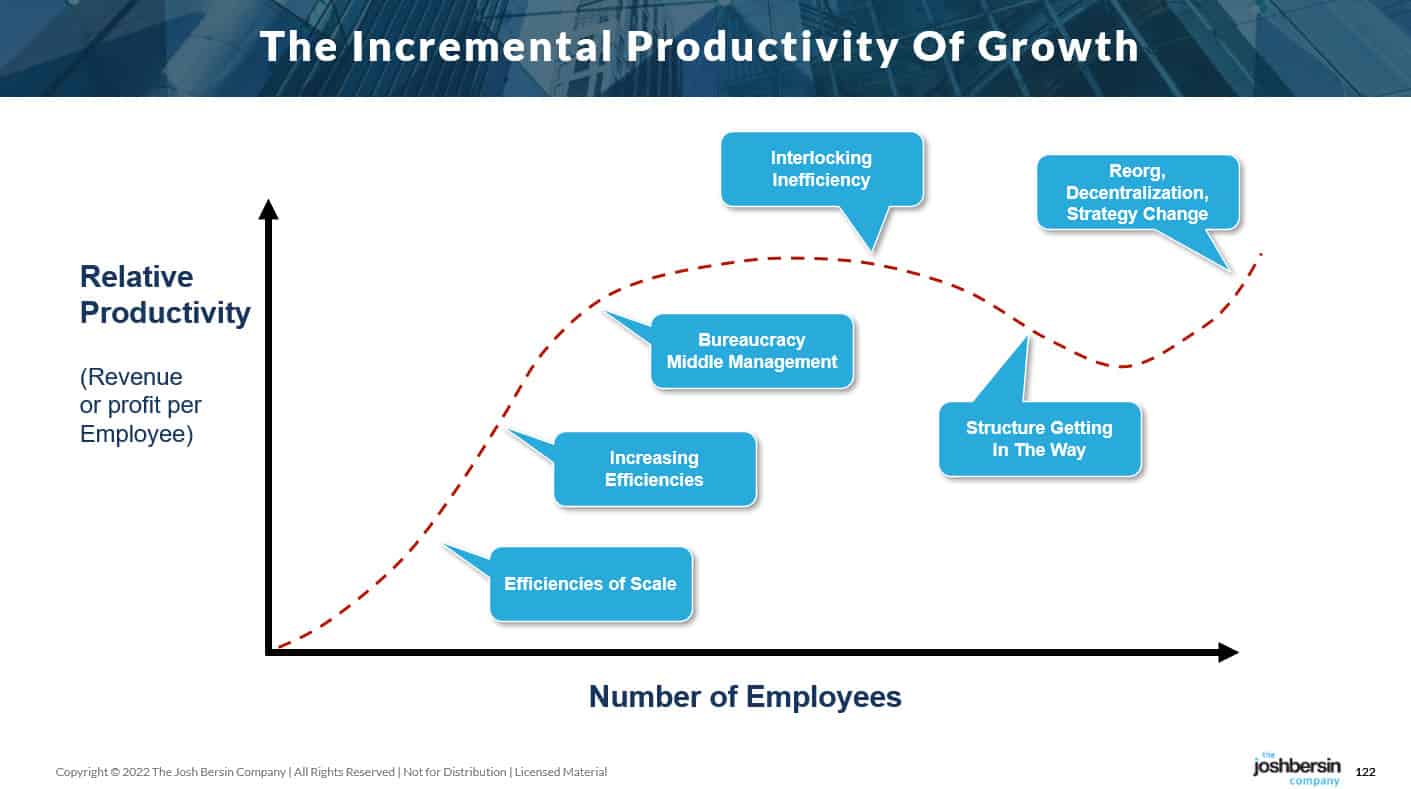

Second, is your hiring strategy increasing productivity or reducing it? And here we get into our research on organization design and the Global Workforce Intelligence Project (all available to corporate members). Consider the chart below.

|

In the growth stage, each employee increases efficiency. An incremental engineer, sales person, or marketing person lets you “divide the work” into more specialized pieces, allowing the “output per hour” to increase as you hire. Yes, a new employee takes 3-6 months to become fully productive, but once that period kicks in the company grows at an incremental rate.

But as this scalable efficiency continues, things start to get in the way. Middle management starts hiring people to “fill seats” and the organization becomes a sprawl. Each line manager asks for more budget, so the company winds up with lots of hard-working people in duplicate roles.

We know this, by the way, from our GWI research. As we analyzed Healthcare and Banking, looking at the top 300 healthcare providers and top 300+ global banks, we found hundreds of jobs in each industry that have the same skills and background but vastly different job titles. (Product managers, project managers, analysts, and so on.) If you don’t constantly look at opportunities to create shared services or standard platforms, productivity per employee starts to lag.

This flattening of the curve, which I show as “bureaucracy” above, is also easy to miss. Most companies know that there’s a lag between hiring and growth, so they hire and wait for productivity to grow. But if you aren’t creating an organization that constantly learns, you end up with a bureaucratic hierarchy before you know it.

Chapters 1 and 2 (Teams not Hierarchy, and Work not Jobs) of my book describe this in detail. At each stage of growth you need to consider “how can we make sure people are operating at the top of their license?” Is this “job” necessary, and how will it make others in the team more productive?

Healthcare companies are quite good at this by the way. They constantly look at operations to make sure highly skilled nurses, doctors, and clinicians are not forced to clean rooms, schedule meetings, or fill out forms.

One of our clients, a large construction equipment manufacturer, was losing market share year after year. They hired product designers, invested in technology and marketing, yet their revenue would not grow. The leadership team asked the product and engineering group to rethink how they’re organized, and the team itself came up with a big idea.

What if, rather than organize ourselves around “products” (drills, sanders, saws, hammers) we organized ourselves around “customer problems?” In the old model each product line had its own marketing, engineering, manufacturing, and sales teams. In the new model the company organized around “home builders,” “cabinet and furniture makers,” and other segments of their customer base. The result was a whole new set of integrated products, and new centralized sales and channel organization. Sales and profit have soared.

Dean Carter, the ex-CHRO of Patagonia, recently told me that their CEO was frustrated that their wetsuits, ocean wear, and waders weren’t driving enough value. He sensed that “organizational sprawl” was happening in product teams. So he reorganized these product owners into “Ocean,” “Mountains,” and “Rivers and Streams.” The new consolidated groups developed more integrated products, each with the goal of making the earth more sustainable.

You can make these decisions too. Keep asking yourself: are we getting more productive or less? Are we pinpointing current market needs, or chasing the old game. Do we have to hire this fast?

I can’t guarantee you’ll never need a layoff, but if you think this way you might avoid the disruption.

Additional Resources

Layoffs.fyi Real Time Update On Tech Layoffs

Elon Musk Is Bad At This (Atlantic Magazine)

“There’s No Good Way To Do This” CEO of Stripe Layoff Letter

Mark Zuckerberg Says “I’m Sorry” To Employees Being Laid Off

Better.com Layoff Via Zoom (what not to do)

The email Elon Musk just sent to Twitter employees is a masterclass in how not to communicate