Why Do Companies Hire Too Many People?

This week we witnessed one of the most amazing business stories in years. Meta announced a 22% reduction in headcount coupled with a 25% increase in revenue, resulting in a net income of $14 Billion, up 203% from the year before. This means Meta, a $160+ billion company, is generating 35% net profit after tax (higher than Google, Apple, or Microsoft.)

This is pretty amazing. The company terminates almost one in four of its staff and the financial results skyrocket (Meta’s market cap went up by $1.7 Billion on Friday).

What are we learning here?

Quite simply that companies can grow at an exceptional rate without hiring so many people.

Why Do Companies Over-Hire?

Let’s take a step back. Why do companies over-hire and how can we avoid it? In the coming years as the job market gets even tighter, companies need to grow without a linear growth in staff. We are entering an age where “over-staffed companies” will underperform lean companies, and this requires a change in thinking.

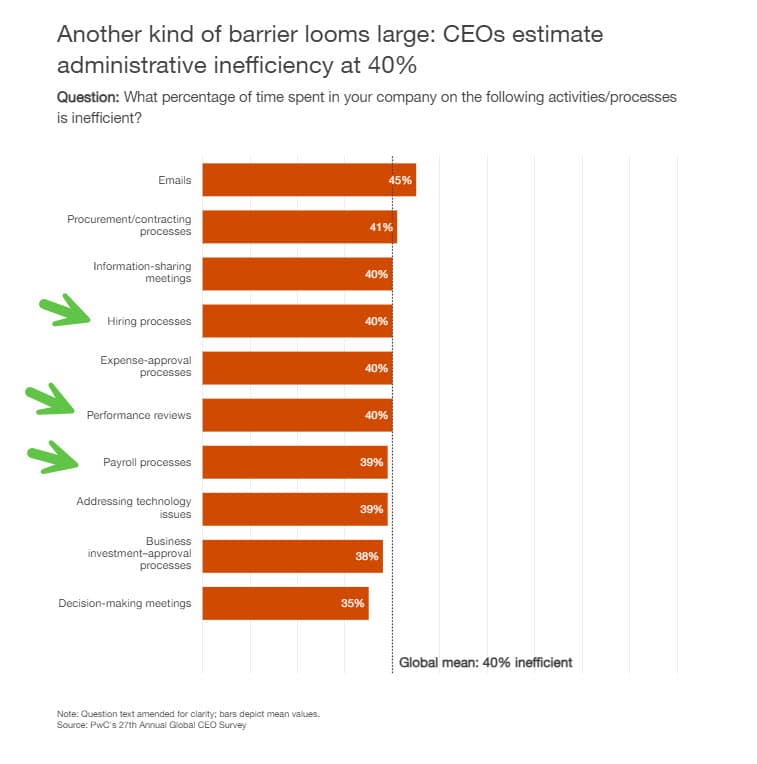

Note, by the way, that the 2024 PwC CEO survey found that C-level execs believe that 40% of their company’s time is wasted on non-essentials. And three of the top ten issues have to do with HR. The same survey also shows that two-third of CEOs believe AI will improve administrative efficiency by 5% or more, and I agree.

|

This is why I talk about “The Global Search For Productivity” in our 2024 Predictions report. We’re entering a time when smaller companies with higher revenues per employee will outperform, out maneuver, and outgrow their large-staff competitors. Slowed by too many layers and challenges in hiring, companies that haven’t learn how to focus their teams (and headcount) will fall behind.

What does this new strategy look like? Here are five big ideas.

#1. Stop thinking that hiring is a strategy for growth.

Many leaders still believe that “hiring more people will make the company grow.” In other words, if you want to “get big fast” (a silicon valley mantra), you hire as fast as you can. More sales people will generate more revenue. More engineers will crank out more products. More marketing people will generate more leads. And more service staff will serve more customers.

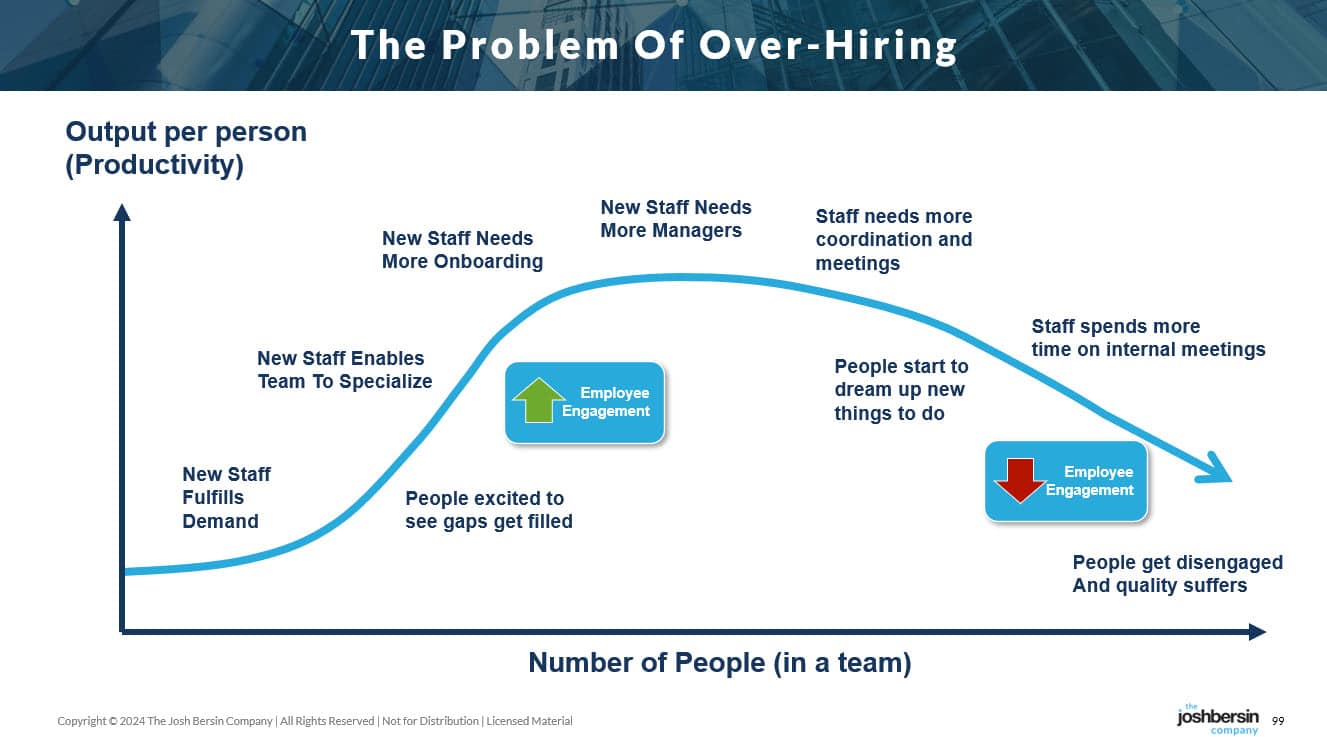

These are flawed assumptions. In every functional area there are high performers (super-powered workers) and lower performers. When you rush to hire you force the recruiters to bring in “bodies” and not focus on fit. The result is what I call the “diminishing productivity of each hire.” Each additional person you hire slows down the others already in place.

Yes companies have to replace people who leave and add staff. But when a company hires quickly the shear volume of onboarding and new people forces managers to slow down, staff to slow down, and many existing processes to slow down. And that means each additional “new hire” reduces productivity overall.

We recently interviewed Panasonic, one of the leading manufacturers of batteries. The senior HR leader discovered (through analysis) that line managers were over-hiring and their output had slowed while employees were booking more overtime. While the managers did not agree (see #2), when she shared the data they suddenly realized the problem.

The data revealed that once a production line had more than 50 people scheduled and staffed, productivity decreased. This was due to the diminishing returns curve, where adding more workers beyond an optimal point resulted in less output per worker.

This overstaffing led to increased costs and also resulted in higher defect rates and material waste, as more people on the line did not necessarily equate to more efficiency or better quality. And the production managers did not believe this until they saw the data directly.

Health care providers are among the most advanced in this domain. Given the enormous shortage of nurses and clinical professionals (upwards of 2 million job shortage in the next three years), these companies automate administrative work, decompose clinical care into sub-specialties, and train nurses to operate at the top of their license.

Providence and Stanford Healthcare, for example, have carefully designed the nursing role (by reducing administrative tasks and using AI for scheduling) to reduce staffing per patient with no decrease in patient outcomes.

|

How do you know you know where you are on this curve?

You can look at revenue or output per employee. When this metric starts to go down, you’re operating at the right side of the curve. And in many organizations we’re already well along the down slope.

I often compare revenue per employee for peer companies in a market segment and the ones with the lower numbers are almost always laggards in their market. This, by the way, is why Private Equity firms almost always let people go as soon as they buy a company.

#2. Redefine how HR handles headcount needs.

The second issue we face is the way most companies hire.

In nearly every company I know there is an annual or quarterly process for headcount allocation. The CFO, knowing that there is unlimited demand from managers for hiring, “releases headcount” to business units based on their financials. These requisitions are distributed to managers and the HR team goes to work.

HR then operates like order takers and the recruitment organization starts processing requisitions. We develop job postings, source candidates, buy ads, and hire recruiters. We start screening, interviewing, and assessing candidates. And a massive effort of scheduling, discussing candidates, and decision-making takes place.

All this effort, which takes valuable time and is rated the #3 “most bureaucratic” process by CEOs, happens without a lot of serious thought.

Should this hire be filled by an internal candidate? Should this job be full time or is it part-time and could be shared? Should this work be outsourced because it’s not strategic? Does this team have high turnover so should we discuss why this position is even open?

These are important, strategic conversations to have, and unless a senior HR business partner (or talent advisor) is involved, they don’t really take place. Hiring managers are the boss and they may not want an HR person asking them all sorts of questions about how they’re running their teams.

So what happens? The Talent Acquisition team rushes to fill the positions and barely has a chance to discuss internal development, job rotations, part-time, or any of these other important options. There is no real process to think about how we “engineer” this team for growth, and the team bulks up on more people.

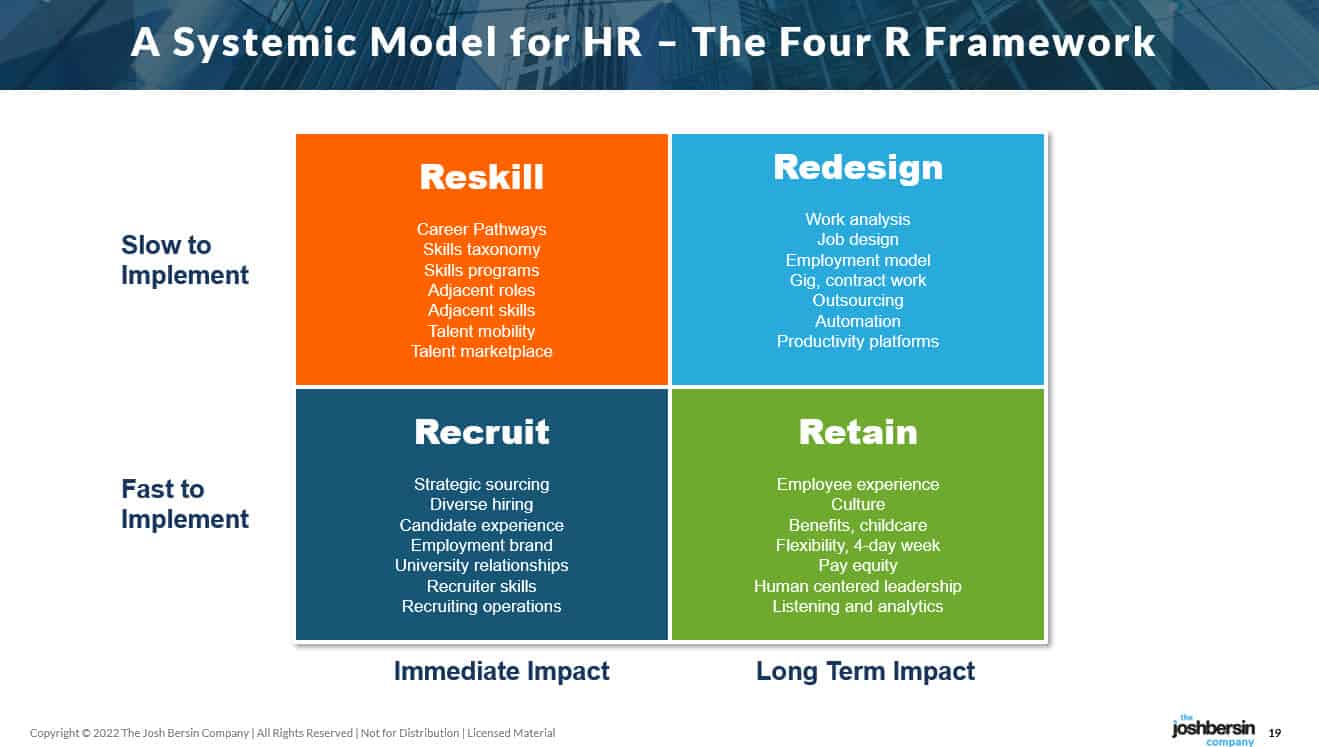

As we discuss in our Systemic HR research, this can all be avoided if we adopt the 4R (Recruit, Retain, Reskill, Redesign) approach to hiring. And this is why more and more recruiting teams are getting integrated with L&D, companies are buying talent marketplace platforms, and most CHROs are pushing hard to improve internal hiring ratios and build an internal career management strategy.

|

#3. Build a strategy, culture, and set of tools for internal mobility.

Many years ago I realized that you could group companies into two types: those who believed in the “up or out” model of work (and they often used stack ranking), and those who believed in the “coaching and development” model of work.

The first type believed in “competitive performance” and always looked at employees as people through a lens of performance. We grouped people into performance buckets and as new opportunities arose, we focused on these “HiPOs” for the important roles.

The second type believed in “continuous learning” and growth mindset, and they provided growth opportunities, developmental assignments, and coaching for everyone. In a sense these companies simply operated in a philosophy that “anyone can be developed to do more,” and they focused on never-ending skills development.

Today, by the way, more than two-thirds of the companies we study are in the second category, but most of them “think and operate” like the first. So we are in a global transition from a model of “perform or get fired” to “perform and we’ll help you grow.”

Well the only way to operate in a labor shortage (it now takes 45 days on average to hire and upwards of 70 days or more for some roles) is to move to the second model. And thanks to AI tools and talent intelligence, we can now figure out that the marketing manager with a math degree in marketing can become a data scientist in a fairly short period of time.

Not everyone wants to change careers, of course, and most of us are afraid of doing something new. But if you want to grow your company without hiring and churning people, and you want to move staff away from under-performing products areas to growth areas, you have to make this work. And the result of strong talent mobility? You don’t have to hire (and fire) in cycles, you build deep and enduring skills, and job satisfaction and retention can skyrocket.

#4. Redefine the role of managers.

Broadly thinking, there are two models of management: managers who operate as supervisors, and managers who operate as “on-the job coaches.” And while this varies by job and role, highly efficient companies have very few leaders who don’t “run things” as well as “do things.”

As the HR leader at WL Gore told me years ago (a pioneer in flat, efficient management), “managers manage projects, people manage themselves.” In other words, if you want to avoid a bloated bureaucracy of middle managers you have to increase span of control and define “management” as that of coaching, project leadership, development, and alignment.

As the HR leader at WL Gore told me years ago (a pioneer in flat, efficient management), “managers manage projects, people manage themselves.” In other words, if you want to avoid a bloated bureaucracy of middle managers you have to increase span of control and define “management” as that of coaching, project leadership, development, and alignment.

As you do this people will step up and take leadership positions in teams. In a sense, the way to free productivity is to “manage less, lead more.”

Great leaders, as our new leadership research found, focus on vision, inspiration, focus, and change. These are roles for special people who can set a direction and help others figure out how to get there. They align teams, help people avoid wasting time, and clearly assign accountability. They embrace and encourage change, and they set an example as someone who will always help and coach others.

While these ideas are well understood, fast-hiring often make this impossible. When I worked in “fast hiring” (not “fast-growth”) companies I found managers who were overwhelmed with people issues: onboarding, training, coaching, and problem solving. When you grow slowly and keep spans of control wide you find that peers step up and take responsibility for these tasks. And this helps the company grow.

Again going back to healthcare. It’s not unusual for a nurse supervisor to have dozens of people reporting to her (or him), since these staff are well trained, clear on their jobs, and highly motivated. This is an example of a highly scalable model, and we all have to work on this transformation all the time.

#5. Focus on your core.

The final, and most important way to avoid “staffing bloat” is to focus. My experience is that organizations (teams or business units) can only focus on two or three things at once.

But focus on what? Most large companies have dozens of projects, hundreds of offerings, and business units all over the world. Well in our HR world, this means doing what I often call “cleaning out the kitchen drawer.” Today, using new AI tools, we can focus our energies on the few things that matter.

This last week we met with several HR leadership teams and many of them have 20 or more projects. While this may sound ambitious, it actually creates inefficiency. You should get together as a leadership team and decide what is essential and what is not. When Meta let 22% of their people go I would guess many projects stopped in their tracks. And as painful as that can be (every major initiative has a sponsor), it enables growth, profitability, and innovation.

Years ago at Sybase (originally a high-performance database company) we entered a period where we had lost focus. The company was developing tools, middleware, industry solutions, and professional services. Senior leaders believed that “becoming a bigger company was better.” But alas this was not to be.

By losing focus on the core database, Microsoft and Oracle caught up. And soon enough the “wood behind the arrow” got weak, our sales and marketing was distracted, and eventually the company was sold.

Last year we interviewed the hiring team at McDonald’s, where the company constantly hires new staff as young people move through their careers. Through a process of “reductionist thinking,” and with the help of Paradox, they reduced their time-to-hire for store positions from 25 days to 6 days. This is a 75% reduction in effort. As a result the recruitment team at McDonalds can focus on hiring quality, targeting, retention, and in-store position management. For McDonald’s, a company that hires some of the most difficult to find positions in the world, this has been a miracle.

Companies have hundreds of opportunities to focus. Get together with your team and prioritize what really matters. When Pepsico asked their employees what was the “most bureaucratic, time-wasting process” in the company during the pandemic (using a crowdsourcing tool they call “the process shredder“), performance management was rated the worst. Every company has things that get in the way, this is the year to point them out.

Bottom Line: Have The Conversation

The bottom line is this. Nobody will initially agree on what’s most important and which team is too big. But you have to have the conversation.

In today’s economy, where it’s harder than ever to hire, an over-staffed company will simply underperform. Remember that “less is more” and help your entire leadership team think about how to drive productivity, reductionism, and focus everywhere you go.

Additional Information

The Dynamic Organization: How To Design For Growth

The Organization Design Superclass: Certificate Program On Agile Team Design