The Economy That Just Won’t Quit: Why Jobs Keep Getting Created

Economist seem baffled about job creation, even in the economic slowdown. This month the US unemployment rate dropped to 3.5%, the lowest level in more than 50 years. The Fed, which keeps raising rates and trying to reduce asset prices, simply cannot stop the growth.

(And this is not only in the US: In Australia the occupations facing skills shortages doubled this year, three-quarters of UK businesses have labor shortages, and Germany now faces one of the biggest labor shortages in history.)

While some of this is due to the economic cycle (and the money pumped into the economy during the pandemic), I believe something bigger is going on. The labor market has fundamentally changed, and we’re probably never going back to the old market again.

There are three big things going on, so let me try to explain.

First, job creation is rampant because of the massive change in industries, technology, and automation. As I’ve talked about in PowerSkills Economy, every job is being automated and upgraded as non-routine work is taken away. Nurses are doing less paperwork; retail workers don’t have to scan orders; and soon software engineers won’t have to write code. We use automated video and transcription for much of our work, so we are hiring more senior analysts every day.

These “new jobs” are not only due to increased demand and economic growth: they’re created by industry transformation. Healthcare, which has become the largest employer in the US, is growing at twice the rate of the economy. So are electric vehicles. Rivian, for example, went from 800 employees to 16,000 employees in only four years. These kinds of industry changes are everywhere, creating demand for “new jobs” and “new skills” regardless of GDP fluctuations.

These “new jobs” are not only due to increased demand and economic growth: they’re created by industry transformation. Healthcare, which has become the largest employer in the US, is growing at twice the rate of the economy. So are electric vehicles. Rivian, for example, went from 800 employees to 16,000 employees in only four years. These kinds of industry changes are everywhere, creating demand for “new jobs” and “new skills” regardless of GDP fluctuations.

(Read our Global Workforce Intelligence research for all the details.)

And as I discuss in our research on PowerSkills, these new jobs are higher paying and more demanding of our human, social, analytic, and creative skills. So this new economy of work is getting better for everyone.

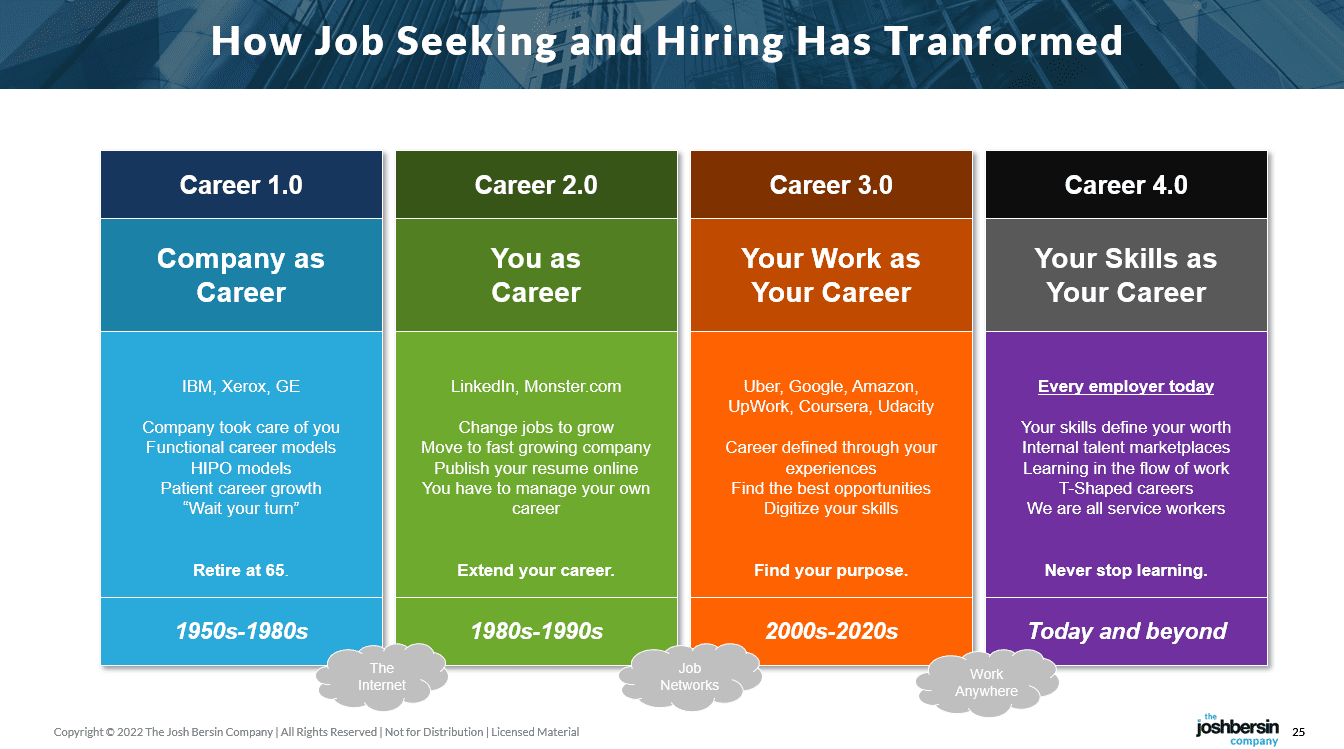

Second, job-seekers are now empowered. I cannot believe how job-seeking has changed.

In the last year more than a third of US workers voluntarily changed jobs. Close to 60 million people decided to change jobs last year (2.7-4% per month) and they are more mobile and empowered than ever. Not only is it easy to look for a job (AI systems like Eightfold or Beamery or Phenom let jobs find you), it’s easy to apply because so many jobs are remote.

And employers no longer look for “experience” to hire. They look for skills, capabilities, and culture – enabling anyone to apply for almost any job they desire. McKinsey’s look at the pandemic discovered that 45% of the people who changed jobs in 2021 actually changed industries. This level of “dynamism” has never been seen before.

|

And post-pandemic, this new level of mobility is paying off. The BLS reported this month that “job switchers” got a 9% raise this year, while “job stayers” got about a 5% raise. So people who move from job to job are being rewarded, even though employers try to hold on to the people they have.

Third, companies will not “lay off workers” as the economy slows, because new areas of demand are created.

Now this is a controversial idea. The traditional thinking by economists is that higher interest rates reduce demand (demand for new house sales has plummeted, as have jobs in investment banking), which in turn creates unemployment. The Phillips Curve, which we all learned about in Economics 101, essentially teaches us that this slowdown in jobs will reduce inflation.

But that whole idea makes no sense when jobs are being invented before our eyes.

Consider this: don’t consider the job market as a bunch of “vacancies waiting to be filled.” Rather it is a dynamic machine, with new jobs being created while others go away. The job seekers, which are essentially the fuel of the machine, used to be limited or blocked by their education, skills, or location. These “blockers” are rapidly going away.

In my case, graduating from college in 1978, I applied for jobs by mailing my paper resume to the “personnel department” of target companies. I interviewed on college campus and hoped I would get an offer. After waiting weeks, a few offers came – and each required a different location, pay, or startup position. I had several offers to consider, but I certainly never felt “empowered.” In fact I read “What Color Is Your Parachute” dozens of times just to figure out what I wanted to do.

Today’s job market is very different. High school grads can write code, become YouTube stars, or work as gig workers with very little risk. They can apply for jobs all over the world (job networks like Handshake are revolutionizing college hiring). And they can learn new skills through online education, boot camps, or career development programs. Employers like Providence Healthcare are training Amazon warehouse workers to become clinical care professionals, jobs that pay six figures in only a few years.

This, my friends, is the new world of work.

As I talk about in my new book (Irresistible: The Seven Secrets Of The World’s Most Enduring, Employee-Focused Organizations) employers that thrive have figured this out. They’re always recruiting, always looking for people with new skills, and always investing in Talent Intelligence to understand the new roles they need.

As I talk about in my new book (Irresistible: The Seven Secrets Of The World’s Most Enduring, Employee-Focused Organizations) employers that thrive have figured this out. They’re always recruiting, always looking for people with new skills, and always investing in Talent Intelligence to understand the new roles they need.

While I read all of Paul Krugman’s columns and most of the economists studying the economy, I sense they are missing something big. The micro-economics of employment have changed. Employers can “signal” the job market easily (posting jobs on LinkedIn or Indeed, using Eightfold or Beamery or Phenom to promote new positions, buying job ads on Google or Facebook). Job seekers can apply for jobs from their phones. And AI can help us define what skills we need, what skills we have, and what development we need to grow.

Yet one big challenge remains: the human fear of finding a new job, changing employers, or learning something new. And that, to me, is the new economic issue we face.

Will workers feel empowered, educated, and informed enough to find these new jobs as they’re created? I once interviewed the CHRO of a large tech company (200,000+ employees) and she told me the sad story of the 10,000 Cobol engineers they were going to lay off. I asked her “why don’t you just retrain these folks?” She said, in a somewhat disappointing way, “we aren’t sure they’re capable of being reskilled.”

That kind of thinking has got to go away. If we keep talking about how “weak the economy” has become, or how many Goldman Sachs bankers were laid off, we will “scare people” away from looking for new positions. And this fear of changing jobs will become the biggest economic barrier we face.

I believe, after decades of work in the study of HR and employers, that the biggest lesson we’ve learned from the pandemic is what I call “The Unquenchable Power Of Human Spirit.” People, regardless of education, race, or age, have a biologic instinct to adapt. Look at the citizens of Ukraine, and how they’ve risen to strike back at their enemies. We, as employers and employees, have to engage, fuel, and admire this spirit – giving people the freedom to grow, change, and find new positions.

Yes, we’re at the end of a 14 year economic cycle, and yes, there will be an economic slowdown. But employers who think just “laying people off” is the answer will simply doom their companies for the next coming cycle. Every downturn is an opportunity to reinvent. And that reinvention is happening faster than you might imagine.

For those who are managers or employees, let me simply state this. The most important skill you have is simply your own human energy. You are capable of doing more than you ever imagined, if you just look around, learn, and reach out to others. I believe the “low unemployment rate” is now a structural reality, and we will be living in a world with opportunity for many years to come.

Additional Resources

Our New Talent Intelligence Primer: What You Need To Know

Understanding The Transformation Taking Place In Healthcare