Building A Company Skills Strategy: Harder (and More Important) Than It Looks

Over the last few months, we’ve spent a lot of time helping companies build their end-to-end skills strategy. And it’s not as easy as it looks.

In this article, I’d like to share a few of the things we’ve discovered.

1/ Skills Strategy is Not A New Topic

Many companies think that building a “skills-based organization” is a new idea. It really isn’t. Companies in energy, telecommunications, oil drilling, retail, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing have done this for decades. My first two years at IBM (in 1980) were focused entirely on building my skills as a systems engineer, and IBM had a skills taxonomy, development framework, and lots of ways to develop.

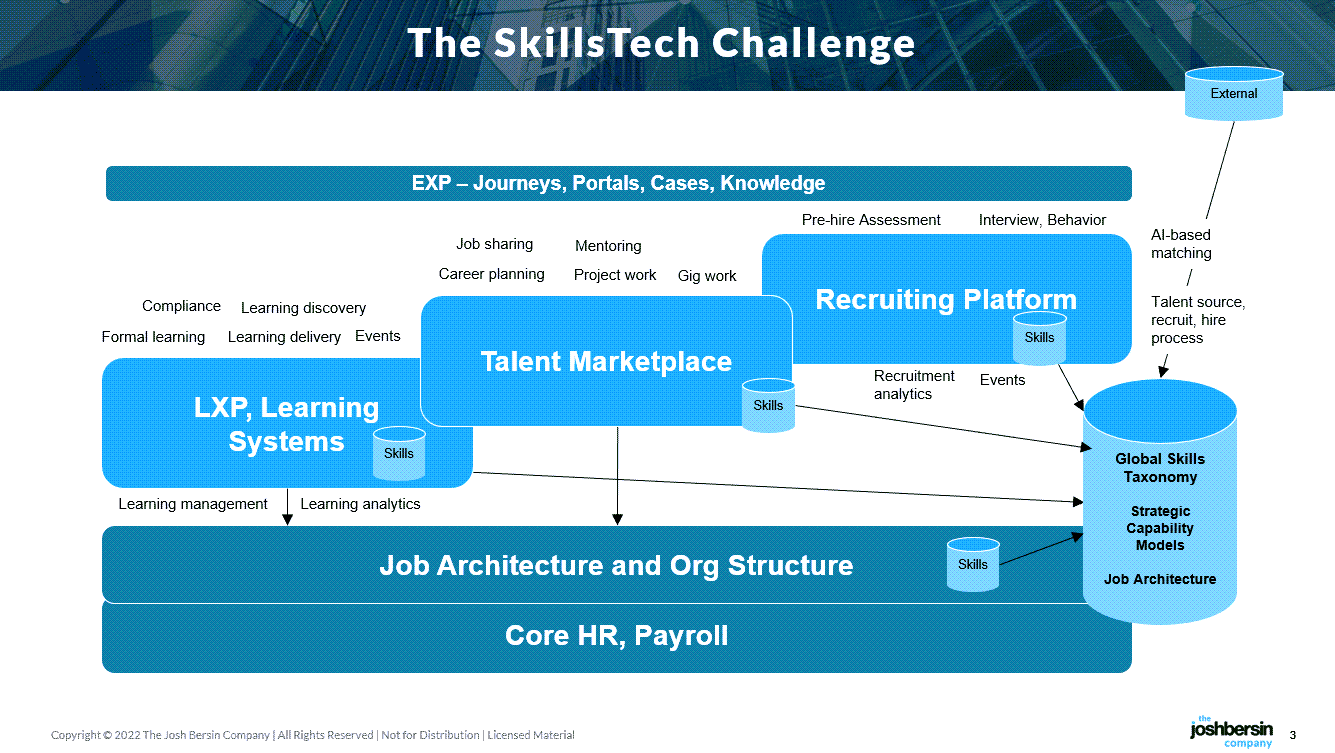

What is new is the technology, applications of AI, and the idea of using skills in an integrated way for recruiting, development, internal mobility, and pay. So while I’m very optimistic and excited about all the SkillsTech being introduced, don’t forget the basics you already know.

For example, many skills applications focus on operational, mandatory skills. As our research on Operational Skills points out, these are situations (operations, medical care, safety) where the employee must verify and certify their skills in order to do their job. Special platforms like Kahuna, SuccessFactors LMS, and Saba were designed for these validated skills, and this area is still growing rapidly.

So as you build your white-collar and professional skills strategy, don’t forget that operations and field teams still need a heavy focus on compliance, certification, and operating skills taxonomies. I suggest you look at these programs you already have before you start all over with some brand new skills cloud project. At A&T, for example, “Pole Climbing” is a vital skill.

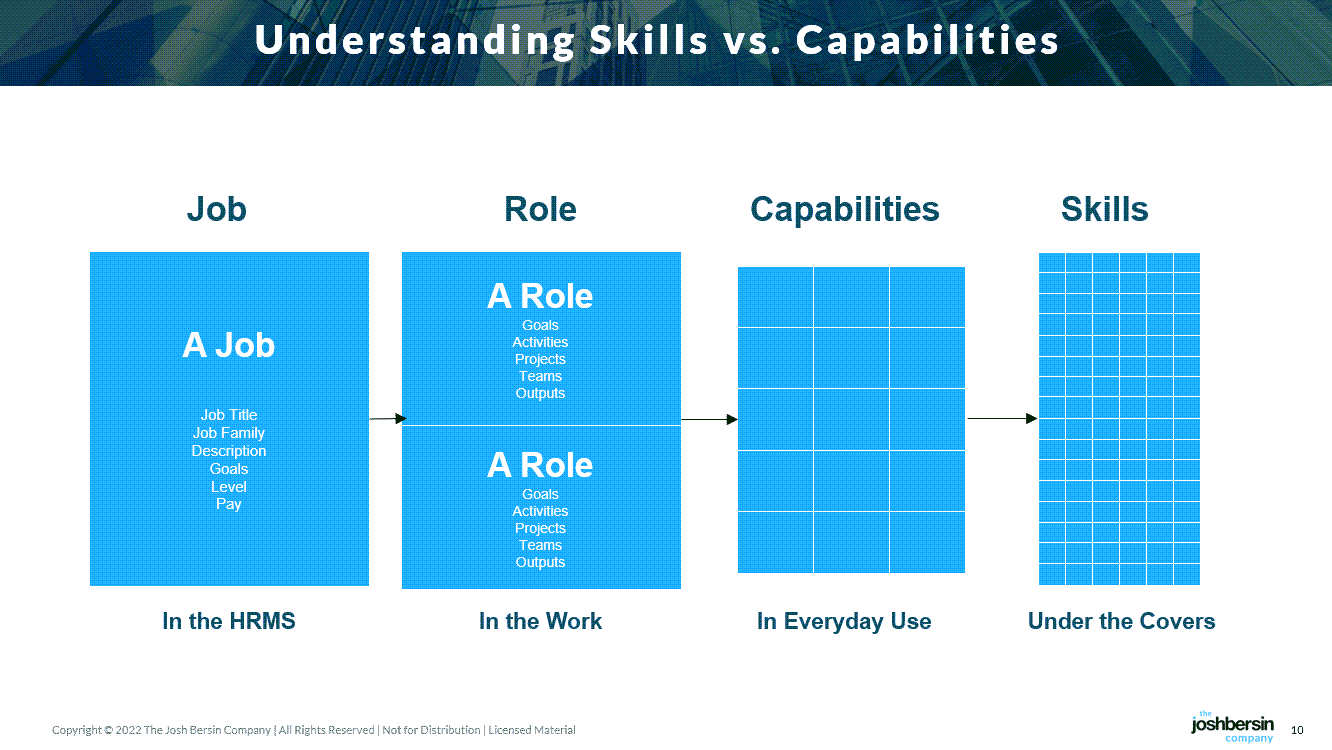

2/ Skills Are Not Capabilities.

While I don’t want to beat this to death, I advise you not to get too excited about the 20,000+ skills that appear when you turn on your LXP or skills-based system. This is essentially a word cloud. These systems infer skills as words, so they often don’t have much context.

For example, when I looked at the skills taxonomy for a major bank I saw “Oracle” as a skill, along with “SQL,” and “Java” and such vague terms as “business acumen” and “analytics.” I also saw “Microsoft Office” and “Tableau.” As you can imagine, these types of vague “skills” don’t tell you a lot. Yes, I may know how to backup an Oracle database (that’s a complex skill in itself), but do I really know all about Oracle as a whole? Of course not.

The solution to this is to add a “capability framework” on top of your skills. In our Global HR Capability Project we defined 90+ “business capabilities” for HR professionals, each of which requires many detailed skills. As I discuss in my latest podcast, just “developing skills” does not make your company perform better. It’s how people use these skills that matters.

The Capability Framework can be developed in a strategic way, through the use of Capability Networks or Capability Academies. These are groups of people organized together to come to an agreement on “what capabilities we need to thrive.” And they will use business language to define these capabilities. Cisco’s sales leadership team has a series of capabilities for executive selling, for example, which of course require skills in building rapport, objection handling, and other more granular skills.

3/ Don’t Try to Boil the Ocean.

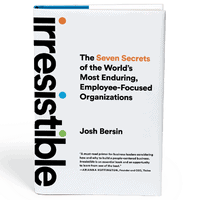

At the risk of taking a controversial position, I wouldn’t advise you to build a skills taxonomy for your whole company at once. Each functional domain needs its own level of detail and subject matter experts involved. Rather, what we see works best is to focus on one of three use-cases (shown below).

|

For a large semiconductor company, for example, the big skills project focused on building deep AI skills so the engineering and design teams could learn the mathematics, algorithms, and use-cases of AI for their next generation of chips. Yes, they need skills models for manufacturing, sales, finance, and everything else. But the big project was focused on a strategic business need, and that work is teaching the company how to do this in other domains in a scalable and repeatable way.

The real message here is that this is not an HR Project. This is a company-wide project that should be broken into functional teams. The group working on sales skills (and capabilities) should be led by sales enablement leaders. The group working on engineering skills (and capabilities) should be led by engineers. You understand.

These “capability networks” or “capability academies” as we call them are powerful, ongoing teams in your company. Once you get them started and come up with common infrastructure and approaches, they will each innovate an add value in unique ways. And your team is there to keep them all aligned.

In fact I believe every large company new needs what I call the “Talent Intelligence COE” (Center of Excellence) so you can help these teams do this in a repeatable way. I’ll talk more about this later.

4/ A Skills Project Is A Job Architecture Project

I don’t want to scare you but there’s no way to dig into skills without hitting the brick wall of your “job architecture.”

|

What this means is that you have to eventually match your “desired skills and capabilities” to the jobs, roles, and careers you embrace. And this is a messy business.

Why? Because most companies proliferate job titles, job descriptions, and job roles. There are often hundreds of jobs with similar roles but different names, and while you may have started with a very standardized set of job titles and families and levels, once you do an acquisition it tends to change. And it gets harder.

Today, as companies evolve into new industries, you have a lot of job titles you don’t fully understand. Does your bank, for example, have Scrum Masters? Does your healthcare company have Informatics Specialists? You get my drift.

The solution is not to try to figure out every job title you need. Rather the opposite. As our work with P&G and other companies has shown, the most scalable solution is to simplify the architecture and remove detailed descriptions from the lower leaf in the job architecture. One internet company I know has the job of “engineer” for all its software engineers. Of course they each do different things, but those “roles” and “responsibilities” are handled at the manager level, not embedded into the job title.

The reason to go in this direction is that it facilitates growth, change, and career mobility. If you crystallize the “state of your company today” in thousands of detailed job descriptions, I can more or less guarantee that in a year almost a third of these will feel out of date. So what do you do, redesign it all again? There’s no point. You want the capability teams and line managers to decide what people do, working with HR to build the right organization design. (We have a fascinating research study and course on org design coming soon.) That way it can change quickly as business needs change.

Also, if you do this carefully, it won’t be so hard for people to move around the company, find a new position, and move up different levels to grow. In IBM’s legacy sales organization where I worked for ten years, there were really only about five major “levels” (many sub-levels for pay grade) and it was very clear where your career could go. Deloitte was very similar.

5/ Assessing And Validating Skills Requires Discussion.

I constantly get asked about this, and honestly, it’s a religious topic. Rather than try to solve it here, let me give you some thoughts.

The level and type of “skills validation” you do depends on the goal you’re trying to achieve. If you are trying to certify people to fix the $5 million pump in the oil refinery, you probably want to certify, validate, and observe these skills before you simply bless someone as “skilled.” Ditto for nurses, doctors, and even financial auditors. And in many of these jobs, there are industry certifications and standards to follow.

But if you want a global process for validating skills that scales, so that everyone in the company has a reasonable skills profile, I’d keep it simple. You can use self-assessment and manager-assessment and it works very well. The way we do it in our Global HR Capability Project is a great example.

We let people self-assess their skills against our capability model in a very simple way. Reflecting the idea that HR is not a “profession” but more like a “craft” (you learn it by doing it, not by taking tests), we ask people to rate their capability level in one of five categories. (And our capability model is designed for this model.)

1=I don’t even know what this is.

2=I’ve done this a few times and I’m familiar, but certainly not an expert.

3=I’ve done this multiple times and can do this well.

4=I’ve done this in multiple companies, industries, and business cases and can design and lead a project.

5=I’m a global expert at this and I could “write the book” or “teach a class” on this.

As you can see, this generic “experience-based” assessment is very easy to understand. And you can actually validate it by asking someone to write a few sentences about the projects, experiences, and insights they have in each capability.

In our case this is incredibly powerful, because more than 8,000 HR people have done this assessment and we can benchmark capabilities by job title, function, geography, industry, and even within a company. Many of our clients use this to build learning journeys and developmental assignments for their HR teams.

Note that this is not going to work if you want “legal certification” that someone knows a particular skill. So you have to decide where you want that level of “certification.”

At Cisco, for example, they used to force salespeople to validate their skills by “demonstrating the skills” to their managers, and then go through peer reviews. They really took sales training seriously. Many pharma companies do this also. It’s all up to you. Just don’t assume that the tool which comes from your tech provider is “the answer.”

6/ External Skills Are as Important as Internal Skills.

Here’s another topic to think about. No matter how well you understand the skills inside your company today, one of the biggest problems you’ll face is the “trending skills” and “competitor skills” you don’t even know about. This is why I believe we have to organize the “Talent Intelligence COE,” not just the “skills architecture team.”

Consider the semiconductor company I mentioned above. They admit that they fell behind in AI-enabled chip design. So they’re trying to catch up as fast as they can. Do they know every AI algorithm, advancement, and machine learning approach they need to learn? Absolutely not. They need to look at external skills data (this is where our Global Workforce Intelligence Project comes in) and carefully see what’s hot, what’s trending, and what’s new.

And this applies in every single domain. I know in HR there are lots of new skills we didn’t talk about two years ago (public health, mental health, resilience, etc). Ford had to build an entire skillset around batteries and electric propulsion over the last five years. Chevron is studying low-carbon energy sources, mining, and solar. You get my drift: this is not only a problem of making your company better at what it does today. It’s a problem of moving your company in the strategic direction it wants to go.

A large defense contractor I work with told us they have annual “capability summits” with their senior business leaders each year, so they can spot the critical new technologies and capabilities they need to build. When drones were first starting they started a deep dive on “drone design and manufacturing capabilities.” They’re now focused on cyber, hypersonic missiles, and lots of stuff we aren’t supposed to know about. Their business depends on knowing “what’s coming around the corner.” And your business does too.

7/ This Requires A Focused Effort And Ongoing Investment.

Finally, let me motivate you to take this effort seriously.

Building a skills and capability strategy is not a problem of “buying a product” and turning it on. This is a serious project that will make your company operate differently.

Once you get started you will see that skills play a role in hiring, mobility, development, diversity, and even pay. Many companies are starting to pay people different hourly rates based on the skills they demonstrate. (Operations teams, nurses, etc. do this regularly.) So I wouldn’t bury this work in L&D – it’s more systemic and strategic than training.

And much of the Talent Intelligence and capability architecture work will fall into strategic planning. If you identify a massive skills gap in detail, you’ll be asked to consider should we buy, build, or acquire these skills?

|

And remember that skills are not a “build and done” project. This is really a capability you build in itself.

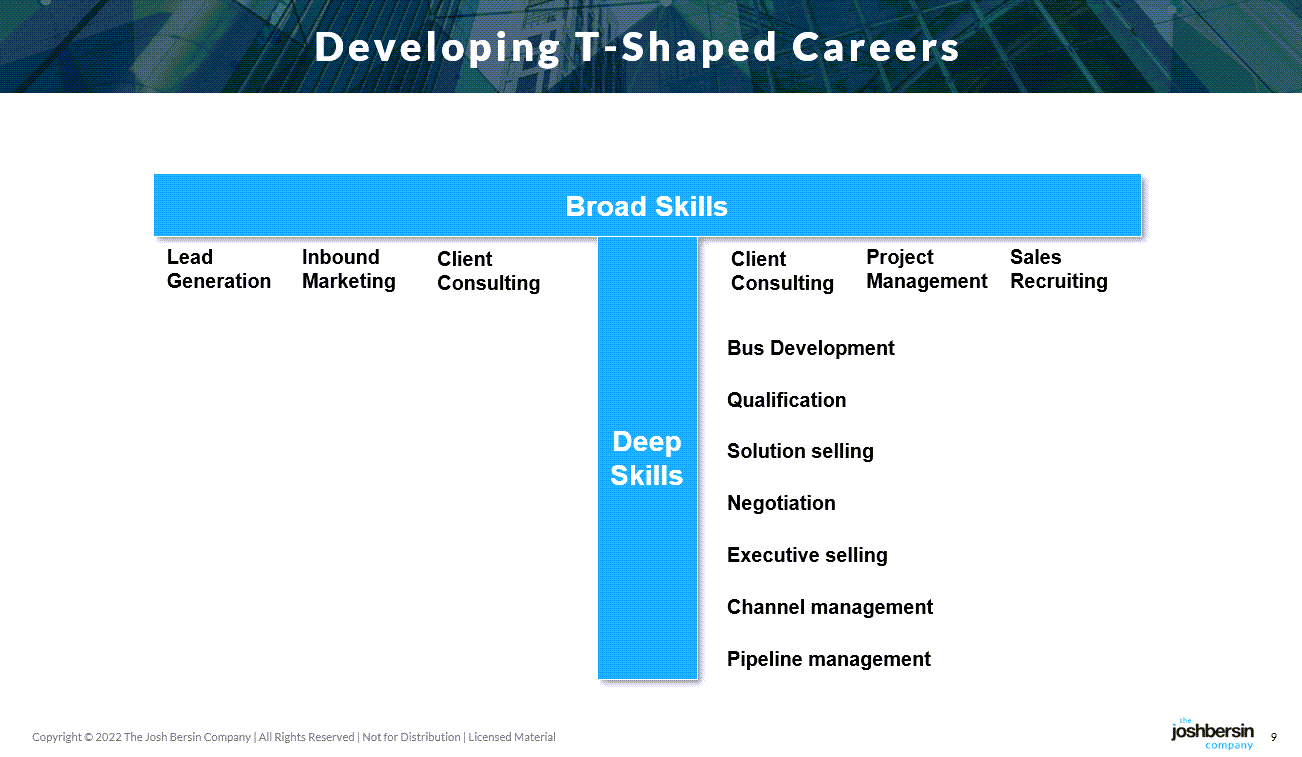

Companies that focus on a growth mindset and learning culture are always thinking about skills, and they understand that nobody becomes proficient by learning one set of skills. As the “T-shaped skills” model points out, we need a flexible set of tools that lets people develop themselves vertically and horizontally. That’s what Capability Academies are all about.

|

We Are Here To Help

We are here to help. I have personally worked with our team to do a lot of this work in the HR profession, and our capability model, assessment, and academy is built around these principles. And we advise companies on this strategy every day.

If you want your company to grow, adapt, and perform in today’s economy, this is a critical initiative for investment. It’s increasingly hard to hire great people, and every great company is inventing “new capabilities” every year. I want to inspire you to focus on this domain, build your strategy over time, and stay pragmatic and “problem-focused” along the way.

Additional Resources

Understanding SkillsTech, One Of The Biggest Markets in Business